Last Updated: September 2021

Advice to the Profession companion documents are intended to provide physicians and physician assistants ("Registrants") with additional information and general advice in order to support their understanding and implementation of the expectations set out in policies. They may also identify some additional best practices regarding specific practice issues.

This document is intended to provide guidance for how the obligations set out in the Complementary and Alternative Medicine policy can be effectively discharged. This document also seeks to provide physicians with practical advice for addressing common issues that arise in practice.

Much of this document is intended to assist physicians who provide complementary or alternative treatments to patients. However, even physicians who do not provide complementary or alternative medicine may be asked questions or have discussions with patients regarding these kinds of treatments. More information on what physicians who do not provide complementary or alternative medicine need to know, can be found towards the end of this document.

What is complementary and alternative medicine?

Complementary and alternative medicine can be described as any treatment that is not part of the conventional medicine that is commonly provided in hospitals and specialty or primary care practices and taught in medical schools, and encompasses a range of therapeutic concepts, practices, and products. This can range from low risk lifestyle change and natural product suggestions, through to medical interventions or procedures that may pose a greater risk of harm to a patient.

Generally, practices like naturopathy, acupuncture, meditation, yoga, reiki, non-contact therapeutic touch, and homeopathy are associated with complementary and alternative medicine.

What is or is not considered complementary and alternative medicine can change over time, as concepts, practices, and products that are proven to be effective are incorporated into conventional medicine.

Some new medical treatments may be subject to other regulatory limits. For example, Health Canada requires that some treatments or therapies be registered with them as part of a clinical trial. Physicians providing this kind of medicine will need to be aware of any other regulatory limits that may apply and comply with them.

Why does the CPSO set out expectations for physicians who provide complementary or alternative medicine?

As the medical regulator in the province of Ontario, the CPSO sets out expectations

for physicians who provide care to patients, whether that care is conventional, complementary, alternative, or integrative.

In order to ensure the provision of quality care, the CPSO aims to strike a balance between protecting patients from harm, while respecting patient choice and autonomy, and not impeding innovation and professional judgment.

At their core, CPSO expectations aim to ensure that:

- physicians act with their patients’ best interests in mind (for instance, by not exposing the patient to unnecessary risk, by being transparent with patients about the risks and benefits of treatments, etc.);

- physicians respect patient choice or autonomy regarding their health care goals and treatment decisions (for instance, by conveying information to and discussing treatments with patients in a non-judgemental way, providing impartial information, etc.); and

- physicians are aware of and take reasonable steps to address patient’s potential vulnerability (for instance, by considering the patient’s individual circumstances or any financial hardship a patient may be experiencing, etc.).

What are the health risks associated with complementary and alternative medicine?

On the basis of the available evidence, some complementary or alternative treatments appear to pose little risk in themselves, however, some can present significant, even life-threatening health risks. This may be, for example, because the treatment itself is inherently risky, or because it is interfering with or replacing the administration of a more effective conventional medical treatment, especially for a serious illness. There are cases where the administration of a treatment as an alternative to a more effective medical treatment has contributed to a patient’s death. These risks are serious and need to be considered carefully in line with the values and principles of medical professionalism and the expectations set out in the policy.

What is the evidence for complementary and alternative medicine?

For both conventional and complementary or alternative medicine, clinical research can help to identify a treatment’s risks and benefits and confirm the extent to which a treatment is effective.

Many complementary or alternative treatments have either not been the subject of randomized controlled clinical trials, or the results of the available research do not convincingly demonstrate any positive effect. There may be very little evidence to support the use of some proposed complementary or alternative treatments. As a result, the full risks and benefits of many such treatments are not always well understood.

The policy requires physicians to only provide complementary or alternative treatments that are informed by evidence and scientific reasoning regarding the efficacy of the treatment. Physicians will need to exercise careful judgment of the evidence to ensure they meet this standard.

What should I consider in evaluating the strength of evidence?

The policy requires that complementary or alternative treatments be informed by evidence and scientific reasoning in order to mitigate the risks associated with providing these treatments.

Recommending a treatment to patients without strong scientific evidence raises several risks, including that:

- it will not be effective,

- it will be less effective than another available treatment (for example, a conventional medical treatment), and/or

- it will have unexpected negative consequences (e.g., side-effects).

Before providing such treatments, physicians must think carefully about the strength of evidence there is for a treatments efficacy and how providing a particular treatment could impact a patient and their health care decisions. For example, where the evidence for a treatment is modest, but the risk of harm to the patient is low and it would be undertaken alongside conventional treatment, it may be appropriate for a physician to provide such treatment. However, where the evidence for the treatment is modest, the risks to the patient are potentially high and it would be provided instead of a conventional treatment, the treatment may be inappropriate. Generally speaking, the higher the potential risk to the patient, the higher the level of evidence required.

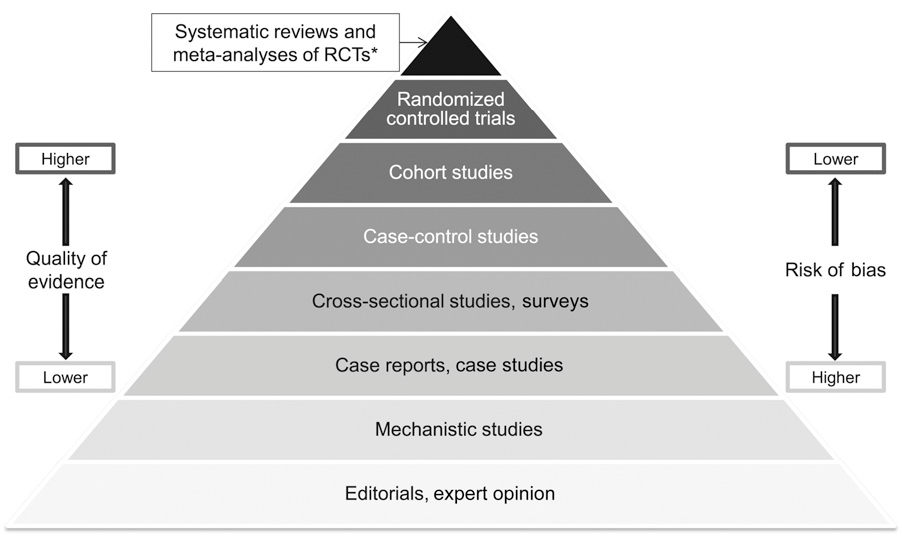

The strength of evidence can be broadly assessed using the hierarchy of evidence below:

-

The diagram depicts a pyramid which represents the hierarchy of evidence that physicians could rely on or consider when providing complementary or alternative medicine. The lowest levels of the pyramid represent lower quality evidence with higher risk of bias, and the upper levels represent higher quality evidence with lower risk of bias.

In order of lowest to highest the pyramid shows: Editorials, expert option; Mechanistic studies; Case reports, case studies; Cross-sectional studies, surveys; Case-control studies; Cohort studies; Randomized control trials; Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized control trials.

While the above diagram shows a generally accepted hierarchy of evidence, the list is not exhaustive, and other types of evidence may be considered.

It will also be important to consider other factors that enhance the strength of evidence, such as:

- objectivity, and based on accepted principles of good research;

- coming from reputable sources (for example, peer-reviewed journals);

- clear demonstration of the therapeutic claims made;

- findings that have been replicated and are consistent across multiple studies; and

- consistency with higher quality studies.

Evidence that would be considered less strong and may not be appropriate to rely on could include:

- studies involving no human subjects;

- before and after studies with little or no control or reference group (e.g. case studies);

- self-assessment studies;

- anecdotal evidence based on observations in practice; and

- patient self reporting.

Less strong evidence may not support offering a treatment at all or may not support offering it to a particular patient after engaging in the risk benefit analysis as set out in the policy.

While these types of evidence may have value in helping to inform a physician’s decision-making, they are less reliable than the evidence produced by the kinds of research outlined in the pyramid above.

The evidence base for many areas of complementary and alternative medicine is constantly evolving so it is important that physicians keep current in terms of the evidence they rely on.

What will the College look at in determining whether it was appropriate for a physician to provide complementary or alternative medicine to a patient?

When the College receives a complaint or a report about a physician providing complementary or alternative medicine, there are a number of factors that will determine the appropriateness of the treatment being provided.

The policy requires physicians to only provide a complementary or alternative treatment to a patient where the benefits of providing the particular treatment outweigh the risks. Physicians need to determine this by weighing a number of factors, including:

- the health status and needs of the patient;

- the strength (e.g. quantity and quality) of evidence and scientific reasoning regarding the effectiveness of the treatment provided for the patient’s symptoms, complaints or condition;

- the potential for harm to the patient;

- any potential interactions between the proposed treatment and any other treatments the patient is currently undertaking; and

- whether the treatment was provided alongside conventional treatment or as an alternative to it.

These factors exist on a spectrum and need to be considered in relation to each other. As outlined above the strength of evidence required to justify providing a particular treatment to a patient will vary depending on the other factors, such as the potential risks to the patient. Where the risks to a patient are low, there will likely be less concern about the treatment being provided, as long as there is compliance with the other provisions in the policy.

Physicians need to be aware that gaining patient consent is not enough on its own to negate the risk benefit analysis. While patients have autonomy to make personal healthcare decisions, there are limits to the kind of treatments it would be appropriate for physicians to provide, regardless of whether the patient consents. Patient consent does not absolve physicians of their responsibility to use professional judgement and only offer treatments that are in the patient’s best interest.

What steps do I need to take to address patient vulnerability when providing complementary or alternative medicine?

Patient vulnerability can vary depending on a variety of factors including the patient’s individual circumstances (such as suffering from a life threatening or terminal illness), or where the cost of treatment may cause financial hardship for the patient.

If your patient is particularly vulnerable or at heightened risk of vulnerability additional steps may be needed to avoid (inadvertently) exploiting them. This could include taking extra care to ensure the patient understands the risks of treatment, providing them with additional resources and information, or giving them additional time to consider their options.

What are the limits for complementary or alternative treatments I as a physician can provide?

Physicians can only provide complementary or alternative treatments to address symptoms, complaints, or conditions that are within their conventional scope of practice to treat, and that they have the knowledge, skills, and judgement to provide. Physicians cannot offer treatments for conditions they would not be able to manage within their conventional scope of practice.

For example, a physician practising orthopedics may use complementary or alternative treatments that could assist with musculoskeletal injuries but would not be able to provide complementary or alternative treatments relating to, for example, pancreatic cancer. Such cancer treatment would not be within that physician’s conventional scope of practice.

Family physicians generally have a wide scope of practice and may help co-manage conditions with specialists. Generally, if the symptom, condition or complaint is something they would ordinarily treat within their conventional scope of practice then, provided they comply with the other provisions of the policy, they can provide complementary or alternative treatments for those same symptoms, conditions or complaints.

Complementary or alternative medicine is not a scope of practice for physicians. The College’s focus is on the practice of medicine, and the role complementary or alternative medicine can play within a physician’s conventional scope of practice. Physicians wishing to practice complementary or alternative medicine more broadly and across traditionally defined scopes of practice, will need to train and credential as a complementary or alternative medicine practitioner.

How does the policy apply to therapies that may be of cultural importance to a specific group (for example, Indigenous traditional healing, traditional Chinese medicine or Ayurvedic medicine) and those who practice such therapies?

This policy applies only to physicians and the services they provide. Nothing in this policy prevents patients from accessing care from other practitioners, including those who provide culturally important healing practices and patients are free to seek care from other practitioners of their choosing.

Additionally, nothing in the policy prevents physicians from incorporating such therapies into their practice, as long as in doing so they meet the provisions set out in the policy. Physicians may also work with other practitioners who provide such therapies.

When providing care, it is important for physicians to recognize that some therapies may be practised within a specific cultural context and have particular importance to certain cultural groups. Providing care in a manner that is culturally competent and respects a patient’s culture, beliefs, lifestyle, healthcare goals and treatment decisions is an important part of medical professionalism.

I am a physician who doesn’t provide complementary or alternative medicine but have patients who use it – what do I need to know?

Complementary and alternative medicine is continually developing. Many physicians may have patients exploring its use and patients are entitled to make treatment decisions and set health care goals in accordance with their own wishes, values, and beliefs. This includes the decision to pursue complementary or alternative medicine.

Some awareness of complementary and alternative medicine would be beneficial and help physicians answer questions patients may have. However, physicians are not required to know about treatment options that are not part of conventional medicine.

Physicians will need to determine what information they feel they are able to provide to a patient based on their knowledge of, and experience with, complementary or alternative medicine.

It is important that physicians inquire about their patients use of complementary or alternative medicine when assessing a patient in order to understand how these treatments may interact with any course of action the physician is recommending. It will also be important for physicians to consider whether they need more information about any treatments a patient says they are undertaking before recommending conventional treatment that may interact with those complementary or alternative treatments.

As stated in the policy, physicians must respect a patient’s choice to pursue complementary or alternative medicine. Patients have the right to make their own healthcare decisions and to pursue treatments outside of those provided by their physician.

What should I do if a patient asks me to refer them to another health care provider based on advice they have received from a complementary or alternative medicine practitioner? Or if I’m asked to order a test for a patient that a complementary or alternative medicine practitioner has told them they need?

Physicians are sometimes approached by patients seeking a referral either on the basis of advice the patient has received from a complementary or alternative medicine practitioner, or to investigate questions or concerns related to complementary or alternative medicine.

Physicians may also be approached by patients seeking diagnostic tests or other clinical investigations related to complementary or alternative medicine. Sometimes a complementary or alternative medicine practitioner may recommend some tests which only a physician can order, or where they would be covered by insurance if ordered by a physician.

It is important that physicians always consider whether such a referral or the ordering of a test or investigation would be in the patient’s best interest, and whether there is a clinical basis for it. However, it is not appropriate for physicians to provide referrals, or order tests or investigations that are not clinically indicated. Physicians who make a referral or order a specific test or investigation are responsible for them and any follow-up that is required (see the Managing Tests policy for more information).

Endnotes

-

While many different concepts, practices and products fall within the term “complementary and alternative medicine” this does not mean that all these concepts, practices or products would be permissible under the Complementary and Alternative Medicine policy. Only those which comply with the provisions of the policy may be acceptable for physicians to provide.

-

Yetley, Elizabeth et al., (2016). Options for basing Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) on chronic disease endpoints: report from a joint US-/Canadian-sponsored working group. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 105. 10.3945/ajcn.116.139097.